en you say 'you'? I work

for Epiphyte Corporation, which is designed from the ground up to work, not

on its own, but as an element in a virtual corporation, kind of like "

"I know what an epiphyte is," she says. "What's two?"

"Okay, good," Randy says, a little off balance. "Two is that the

extension of the North Luzon Festoon is just the first of what we hope will

be several linkups. We want to lay a lot of cable, eventually, into

Corregidor."

Some kind of machinery behind Amy's eyes begins to hum. The message is

clear enough. There will be work aplenty for Semper Marine, if they handle

this first job well.

"In this case, the entity that's doing the work is a joint venture

including us, FiliTel, 24 Jam, and a big Nipponese electronics company,

among others."

"What does 24 Jam have to do with it? They're convenience stores."

"They're the retail outlet the distribution system for Epiphyte's

product."

"And that is?"

"Pinoy grams." Randy manages to suppress the urge to tell her that the

name is trademarked.

"Pinoy grams?"

"Here's how it works. You are an Overseas Contract Worker. Before you

leave home for Saudi or Singapore or Seattle or wherever, you buy or rent a

little gizmo from us. It's about the size of a paperback book and encases a

thimble sized video camera, a tiny screen, and a lot of memory chips. The

components come from all over the place they are shipped to the free port at

Subic and assembled in a Nipponese plant there. So they cost next to

nothing. Anyway, you take this gizmo overseas with you. Whenever you feel

like communicating with the folks at home, you turn it on, aim the camera at

yourself and record a little video greeting card. It all goes onto the

memory chips. It's highly compressed. Then you plug the gizmo into a phone

line and let it work its magic."

"What's the magic? It sends the video down the phone line?"

"Right."

"Haven't people being messing around with video phones for a long

time?''

"The difference here is our software. We don't try to send the video in

real time that's too expensive. We store the data at central servers, then

take advantage of lulls, when traffic is low through the undersea cables,

and shoot the data down those cables when time can be had cheap. Eventually

the data winds up at Epiphyte's facility in Intramuros. From there we can

use wireless technology to send the data to 24 Jam stores all over Metro

Manila. The store just needs a little pie plate dish on the roof, and a

decoder and a regular VCR down behind the counter. The Pinoy gram is

recorded on a regular videotape. Then, when Mom comes in to buy eggs or Dad

comes in to buy cigarettes, the storekeeper says, 'Hey, you got a Pinoy gram

today,' and hands them the videotape. They can take it home and get the

latest news from their child overseas. When they're done, they bring the

videotape back to 24 Jam for reuse."

About halfway through this, Amy understands the basic concept, looks

out the window again and begins trying to work a fragment of breakfast out

of her teeth with the tip of her tongue. She does it with her mouth

tastefully closed, but it seems to occupy her thoughts more than the

explanation of Pinoy grams.

Randy is gripped by a crazy, unaccountable desire not to bore Amy. It's

not that he is getting a crush on her, because he puts the odds at fifty

fifty that she's a lesbian, and he knows better. She is so frank, so

guileless, that he feels he could confide anything in her, as an equal.

This is why he hates business. He wants to tell everyone everything. He

wants to make friends with people.

"So, let me guess," she says, "you are the guy doing the software."

"Yeah," he admits, a little defensive, "but the software is the only

interesting part of this whole project. All the rest is making license

plates.''

That wakes her up a little. "Making license plates?"

"It's an expression that my business partner and I use," Randy says.

"With any job, there's some creative work that needs to be done new

technology to be developed or whatever. Everything else ninety nine percent

of it is making deals, raising capital, going to meetings, marketing and

sales. We call that stuff making license plates."

She nods, looking out the window. Randy is on the verge of telling her

that Pinoy grams are nothing more than a way to create cash flow, so that

they can move on to part two of the business plan. He is sure that this

would elevate his stature beyond that of dull software boy. But Amy puffs

sharply across the top of her coffee, like blowing out a candle, and says,

"Okay. Thanks. I guess that was worth the three packs of cigarettes."

Chapter 11 NIGHTMARE

Bobby Shaftoe has become a connoisseur of nightmares.

Like a fighter pilot ejecting from a burning plane, he has just been

catapulted out of an old nightmare, and into a brand new, even better one.

It is creepy and understated; no giant lizards here.

It begins with heat on his face. When you take enough fuel to push a

fifty thousand ton ship across the Pacific Ocean at twenty five knots, and

put it all in one tank and the Nips fly over and torch it all in a few

seconds, while you stand close enough to see the triumphant grins on the

pilots' faces, then you can feel the heat on your face in this way.

Bobby Shaftoe opens his eyes, expecting that, in so doing, he is

raising the curtain on a corker of a nightmare, probably the final moments

of Torpedo Bombers at Two O'Clock! (his all time favorite) or the surprise

beginning of Strafed by Yellow Men XVII.

But the sound track to this nightmare does not seem to be running. It

is as quiet as an ambush. He is sitting up in a hospital bed surrounded by a

firing squad of hot klieg lights that make it difficult to see anything

else. Shaftoe blinks and focuses on an eddy of cigarette smoke hanging in

the air, like spilled fuel oil in a tropical cove. It sure smells good.

A young man is sitting near his bed. All that Shaftoe can see of this

man is an asymmetrical halo where the lights glance from the petroleum glaze

on his pompadour. And the red coal of his cigarette. As he looks more

carefully he can make out the silhouette of a military uniform. Not a Marine

uniform. Lieutenant's bars gleam on his shoulders, light shining through

double doors.

"Would you like another cigarette?" the lieutenant says. His voice is

hoarse but weirdly gentle.

Shaftoe looks down at his own hand and sees the terminal half inch of a

Lucky Strike wedged between his fingers.

'Ask me a tough one," he manages to say. His own voice is deep and

skirted, like a gramophone winding down.

The butt is swapped for a new one. Shaftoe raises it to his lips. There

are bandages on that arm, and underneath them, he can feel grievous wounds

trying to inflict pain. But something is blocking the signals.

Ah, the morphine. It can't be too bad of a nightmare if it comes with

morphine, can it?

"You ready?" the voice says. God damn it, that voice is familiar.

"Sir, ask me a tough one, sir!" Shaftoe says.

"You already said that."

"Sir, if you ask a Marine if he wants another cigarette, or if he's

ready, the answer is always the same, sir!"

"That's the spirit," the voice says. "Roll film."

A clicking noise starts up in the outer darkness beyond the klieg light

firmament. "Rolling," says a voice.

Something big descends towards Shaftoe. He flattens himself into the

bed, because it looks exactly like the sinister eggs laid in midair by Nip

dive bombers. But then it stops and just hovers there.

"Sound," says another voice.

Shaftoe looks harder and sees that it is not a bomb but a large bullet

shaped microphone on the end of a boom.

The lieutenant with the pompadour leans forward now, instinctively

seeking the light, like a traveler on a cold winter's night.

It is that guy from the movies. What's his name. Oh, yeah!

Ronald Reagan has a stack of three by five cards in his lap. He skids

up a new one: "What advice do you, as the youngest American fighting man

ever to win both the Navy Cross and the Silver Star, have for any young

Marines on their way to Guadalcanal?"

Shaftoe doesn't have to think very long. The memories are still as

fresh as last night's eleventh nightmare: ten plucky Nips in Suicide Charge!

"Just kill the one with the sword first."

"Ah," Reagan says, raising his waxed and penciled eyebrows, and cocking

his pompadour in Shaftoe's direction. "Smarrrt – you target them

because they're the officers, right?"

"No, fuckhead!" Shaftoe yells. "You kill 'em because they've got

fucking swords! You ever had anyone running at you waving a fucking sword ?"

Reagan backs down. He's scared now, sweating off some of his makeup,

even though a cool breeze is coming in off the bay and through the window.

Reagan wants to turn tail and head back down to Hollywood and nail a

starlet fast. But he's stuck here in Oakland, interviewing the war hero. He

flips through his stack of cards, rejects about twenty in a row. Shaftoe's

in no hurry, he's going to be flat on his back in this hospital bed for

approximately the rest of his life. He incinerates half of that cigarette

with one long breath, holds it, blows out a smoke ring.

When they fought at night, the big guns on the warships made rings of

incandescent gas. Not fat doughnuts but long skinny ones that twisted around

like lariats. Shaftoe's body is saturated with morphine. His eyelids

avalanche down over his eyes, blessing those orbs that are burning and

swollen from the film lights and the smoke of the cigarettes. He and his

platoon are racing an incoming tide, trying to get around a headland. They

are Marine Raiders and they have been chasing a particular unit of Nips

across Guadalcanal for two weeks, whittling them down. As long as they're in

the neighborhood, they've been ordered to make their way to a certain point

on the headland from which they ought to be able to lob mortar rounds

against the incoming Tokyo Express. It is a somewhat harebrained and

reckless tactic, but they don't call this Operation Shoestring for nothing;

it is all wacky improvisation from the get go. They are behind schedule

because this paltry handful of Nips has been really tenacious, setting

ambushes behind every fallen log, taking potshots at them every time they

come around one of these headlands. . .

Something clammy hits him on the forehead: it is the makeup artist

taking a swipe at him. Shaftoe finds himself back in the nightmare within

which the lizard nightmare was nested.

"Did I tell you about the lizard?" Shaftoe says.

"Several times," his interrogator says. "This'll just take another

minute." Ronald Reagan squeezes a fresh three by five card between thumb and

forefinger, fastening onto something a little less emotional: "What did you

and your buddies do in the evenings, when the day's fighting was done?"

"Pile up dead Nips with a bulldozer," Shaftoe says, "and set fire to

'em. Then go down to the beach with a jar of hooch and watch our ships get

torpedoed."

Reagan grimaces. "Cut!" he says, quietly but commanding. The clicking

noise of the film camera stops.

"How'd I do?" Bobby Shaftoe says as they are squeegeeing the Maybelline

off his face, and the men are packing up their equipment. The klieg lights

have been turned off, clear northern California light streams in through the

windows. The whole scene looks almost real, as if it weren't a nightmare at

all.

"You did great," Lieutenant Reagan says, without looking him in the

eye. "A real morale booster." He lights a cigarette. "You can go back to

sleep now."

"Haw!" Shaftoe says. "I been asleep the whole time. Haven't I?"

***

He feels a lot better once he gets out of the hospital. They give him a

couple of weeks of leave, and he goes straight to the Oakland station and

hops the next train for Chicago. Fellow passengers recognize him from his

newspaper pictures, buy him drinks, pose with him for snap shots. He stares

out the windows for hours, watching America go by, and sees that all of it

is beautiful and clean. There might be wildness, there might be deep forest,

there might even be grizzly bears and mountain lions, but it is cleanly

sorted out, and the rules (don't mess with bear cubs, hang your food from a

tree limb at night) are well known, and published in the Boy Scout Manual.

In those Pacific islands there is too much that is alive, and all of it is

in a continual process of eating and being eaten by something else, and once

you set foot in the place, you're buying into the deal. Just sitting in that

train for a couple of days, his feet in clean white cotton socks, not being

eaten alive by anything, goes a long way towards clearing his head up. Only

once, or possibly two or three times, does he really feel the need to lock

himself in the can and squirt morphine into his arm.

But when he closes his eyes, he finds himself on Guadalcanal, sloshing

around that last headland, racing the incoming tide. The big waves are

rolling in now, picking up the men and slamming them into rocks.

Finally they turn the corner and see the cove: just a tiny notch in the

coast of Guadalcanal. A hundred yards of tidal mudflats backed up by a

cliff. They will have to get across those mudflats and establish a foothold

on the lower part of the cliff if they aren't going to be washed out to sea

by the tide.

The Shaftoes are Tennessee mountain people miners, among other things.

About the time Nimrod Shaftoe went to the Philippines, a couple of his

brothers moved up to western Wisconsin to work in lead mines. One of them

Bobby's grandpa became a foreman. Sometimes he would go to Oconomowoc to pay

a visit to the owner of the mine, who had a summer house on one of the

lakes. They would go out in a boat and fish for pike. Frequently the mine

owner's neighbors owners of banks and breweries would come along. That is

how the Shaftoes moved to Oconomowoc, and got out of mining, and became

fishing and hunting guides. The family has been scrupulous about holding on

to the ancestral twang, and to certain other traditions such as military

service. One of his sisters and two of his brothers are still living there

with Mom and Dad, and his two older brothers are in the Army. Bobby's not

the first to have won a Silver Star, though he is the first to have won the

Navy Cross.

Bobby goes and talks to Oconomowoc's Boy Scout troop. He gets to be

grand marshal of the town parade. Other than that, he hardly budges from the

house for two weeks. Sometimes he goes out into the yard and plays catch

with his kid brothers. He helps Dad fix up a rotten dock. Guys and gals from

his high school keep coming round to visit, and Bobby soon learns the trick

that his father and his uncles and granduncles all knew, which is that you

never talk about the specifics of what happened over there. No one wants to

hear about how you dug half of your buddy's molars out of your leg with the

point of a bayonet. All of these kids seem like idiots and lightweights to

him now. The only person he can stand to be around is his great grandfather

Shaftoe, ninety four years of age and sharp as a tack, who was there at

Petersburg when Burnside blew a huge hole in the Confederate lines with

buried explosives and sent his men rushing into the crater where they got

slaughtered. He never talks about it, of course, just as Bobby Shaftoe never

talks about the lizard.

Soon enough his time is up, and then he gets a grand sendoff at the

Milwaukee train station, hugs Mom, hugs Sis, shakes hands with Dad and the

brothers, hugs Mom again, and he's off.

Bobby Shaftoe knows nothing of his future. All he knows is that he has

been promoted to sergeant, detached from his former unit (no great

adjustment, since he is the only surviving member of his platoon) and

reassigned to some unheard of branch of the Corps in Washington, D.C.

D.C.'s a busy place, but last time Bobby Shaftoe checked the

newspapers, there wasn't any combat going on there, and so it's obvious he's

not going to get a combat job. He's done his bit anyway, killed many more

than his share of Nips, won his medals, suffered from his wounds. As he

lacks administrative training, he expects that his new assignment will be to

travel around the country being a war hero, raising morale and suckering

young men into joining the Corps.

He reports, as ordered, to Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. It's the

Corps's oldest post, a city block halfway between the Capitol and the Navy

Yard, a green quadrangle where the Marine Band struts and the drill team

drills. He half expects to see strategic reserves of spit and of polish

stored in giant tanks nearby.

Two Marines are in the office: a major, who is his new, nominal

commanding officer, and a colonel, who looks and acts like he was born here.

It is shocking beyond description that two such personages would be there to

greet a mere sergeant. Must be the Navy Cross that got their attention. But

these Marines have Navy Crosses of their own two or three apiece.

The major introduces the colonel in a way that doesn't really explain a

damn thing to Shaftoe. The colonel says next to nothing; he's there to

observe. The major spends a while fingering some typewritten documents.

"Says right here you are gung ho."

"Sir, yes sir!"

"What the hell does that mean?"

"Sir, it is a Chinese word! There's a Communist there, name of Mao, and

he's got an army. We tangled with 'em on more'n one occasion, sir. Gung ho

is their battle cry, it means 'all together' or something like that, so

after we got done kicking the crap out of them, sir, we stole it from them,

sir!"

"Are you saying you have gone Asiatic like those other China Marines,

Shaftoe?"

"Sir! On the contrary, sir, as I think my record demonstrates, sir!"

"You really think that?" the major says incredulously. "We have an

interesting report here on a film interview that you did with some soldier

(1) named Lieutenant Reagan."

"Sir! This Marine apologizes for his disgraceful behavior during that

interview, sir! This Marine let down himself and his fellow Marines, sir!"

"Aren't you going to give me an excuse? You were wounded. Shell

shocked. Drugged. Suffering from malaria."

"Sir! There is no excuse, sir!"

The major and the colonel nod approvingly at each other.

This "sir, yes sir" business, which would probably sound like horseshit

to any civilian in his right mind, makes sense to Shaftoe and to the

officers in a deep and important way. Like a lot of others, Shaftoe had

trouble with military etiquette at first. He soaked up quite a bit of it

growing up in a military family, but living the life was a different matter.

Having now experienced all the phases of military existence except for the

terminal ones (violent death, court martial, retirement), he has come to

understand the culture for what it is: a system of etiquette within which it

becomes possible for groups of men to live together for years, travel to the

ends of the earth, and do all kinds of incredibly weird shit without killing

each other or completely losing their minds in the process. The extreme

formality with which he addresses these officers carries an important

subtext: your problem, sir, is deciding what you want me to do, and my

problem, sir, is doing it. My gung ho posture says that once you give the

order I'm not going to bother you with any of the details and your half of

the bargain is you had better stay on your side of the line, sir, and not

bother me with any of the chickenshit politics that you have to deal with

for a living. The implied responsibility placed upon the officer's shoulders

by the subordinate's unhesitating willingness to follow orders is a

withering burden to any officer with half a brain, and Shaftoe has more than

once seen seasoned noncoms reduce green lieutenants to quivering blobs

simply by standing before them and agreeing, cheerfully, to carry out their

orders.

"This Lieutenant Reagan complained that you kept trying to tell him a

story about a lizard," the major says.

"Sir! Yes, sir! A giant lizard, sir! An interesting story, sir!"

Shaftoe says.

"I don't care," the major says. "The question is, was it an appropriate

story to tell in that circumstance?"

"Sir! We were making our way around the coast of the island, trying to

get between these Nips and a Tokyo Express landing site, sir!..." Shaftoe

begins.

"Shut up!"

"Sir! Yes sir!"

There is a sweaty silence that is finally broken by the colonel. "We

had the shrinks go over your statement, Sergeant Shaftoe."

''Sir! Yes, sir?''

"They are of the opinion that the whole giant lizard thing is a classic

case of projection."

"Sir! Could you please tell me what the hell that is, sir!"

The colonel flushes, turns his back, peers through blinds at sparse

traffic out on Eye Street. "Well, what they are saying is that there really

was no giant lizard. That you killed that Jap (2) in hand to hand

combat. And that your memory of the giant lizard is basically your id coming

out."

''Id, sir!''

"That there is this id thing inside your brain and that it took over

and got you fired up to kill that Jap bare handed. Then your imagination

dreamed up all this crap about the giant lizard afterwards, as a way of

explaining it."

"Sir! So you are saying that the lizard was just a metaphor, sir!"

"Yes."

"Sir! Then I would respectfully like to know how that Nip got chewed in

half, sir!"

The colonel screws up his face dismissively. "Well, by the time you

were rescued by that coastwatcher, Sergeant, you had been in that cove for

three days along with all of those dead bodies. And in that tropical heat

with all those bugs and scavengers, there was no way to tell from looking at

that Jap whether he had been chewed up by a giant lizard or run through a

brush chipper, if you know what I mean."

"Sir! Yes I do, sir!"

The major goes back to the report. "This Reagan fellow says that you

also repeatedly made disparaging comments about General MacArthur."

"Sir, yes sir! He is a son of a bitch who hates the Corps, sir! He is

trying to get us all killed, sir!"

The major and the colonel look at each other. It is clear that they

have, wordlessly, just arrived at some decision.

"Since you insist on reenlisting, the typical thing would be to have

you go around the country showing off your medals and recruiting young men

into the Corps. But this lizard story kind of rules that out."

"Sir! I do not understand, sir!"

"The Recruitment Office has reviewed your file. They have seen Reagan's

report. They are nervous that you are going to be in West Bumfuck, Arkansas,

riding in the Memorial Day parade in your shiny dress uniform, and suddenly

you are going to start spouting all kinds of nonsense about lizards and

scare everyone shitless and put a kink in the war effort."

"Sir! I respectfully "

"Permission to speak denied," the major says. "I won't even get into

your obsession with General MacArthur."

"Sir! The general is a murdering "

"Shut up!"

"Sir! Yes sir!"

"We have another job for you, Marine."

"Sir! Yes sir!"

"You're going to be part of something very special."

"Sir! The Marine Raiders are already a very special part of a very

special Corps, sir!"

"That's not what I mean. I mean that this assignment is . . . unusual."

The major looks over at the colonel. He is not sure how to proceed.

The colonel puts his hand in his pocket, jingles coins, then reaches up

and checks his shave.

"It is not exactly a Marine Corps assignment," he finally says. "You

will be part of a special international detachment. An American Marine

Raider platoon and a British Special Air Services squadron, operating

together under one command. A bunch of tough hombres who've shown they can

handle any assignment, under any conditions. Is that a fair description of

you, Marine?"

''Sir! Yes, sir!''

"It is a very unusual setup," the colonel muses, "not the kind of thing

that military men would ever dream up. Do you know what I'm saying,

Shaftoe?"

"Sir, no sir! But I do detect a strong odor of politics in the room

now, sir!"

The colonel gets a little twinkle in his eye, and glances out the

window towards the Capitol dome. "These politicians can be real picky about

how they get things done. Everything has to be just so. They don't like

excuses. Do you follow me, Shaftoe?"

''Sir! Yes, sir!''

"The Corps had to fight to get this. They were going to make it an Army

thing. We pulled a few strings with some former Naval persons in high

places. Now the assignment is ours. Some would say, it is ours to screw up.

"Sir! The assignment will not be screwed up, sir!"

"The reason that son of a bitch MacArthur is killing Marines like flies

down in the South Pacific is because sometimes we don't play the political

game that well. If you and your new unit do not perform brilliantly, that

situation will only worsen."

''Sir! You can rely on this Marine, sir!''

"Your commanding officer will be Lieutenant Ethridge. An Annapolis man.

Not much combat experience, but knows how to move in the right circles. He

can run interference for you at the political level. The responsibility for

getting things done on the ground will be entirely yours, Sergeant Shaftoe."

''Sir! Yes , sir!''

"You'll be working closely with British Special Air Service. Very good

men. But I want you and your men to outshine them."

"Sir! You can count on it, sir!"

"Well, get ready to ship out, then," the major says. "You're on your

way to North Africa, Sergeant Shaftoe."

Chapter 12 LONDINIUM

The massive British coinage clanks in his pocket like pewter dinner

plates. Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse walks down a street wearing the

uniform of a commander in the United States Navy. This must not be taken to

imply that he is actually a commander, or indeed that he is even in the

Navy, though he is. The United States part is, however, a safe bet, because

every time he arrives at a curb, he either comes close to being run over by

a shooting brake or he falters in his stride; diverts his train of thought

onto a siding, much to the disturbance of its passengers and crew; and

throws some large part of his mental calculation circuitry into the job of

trying to reflect his surroundings through a large mirror. They drive on the

left side of the street here.

He knew about that before he came. He had seen pictures. And Alan had

complained of it in Princeton, always nearly being run over as, lost in

thought, he stepped off curbs looking the wrong way.

The curbs are sharp and perpendicular, not like the American smoothly

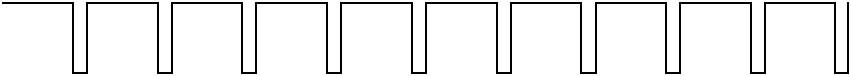

molded sigmoid cross section curves. The transition between the side walk

and the street is a crisp vertical. If you put a green lightbulb on

Waterhouse's head and watched him from the side during the blackout, his

trajectory would look just like a square wave traced out on the face of a

single beam oscilloscope: up, down, up, down. If he were doing this at home,

the curbs would be evenly spaced, about twelve to the mile, because his home

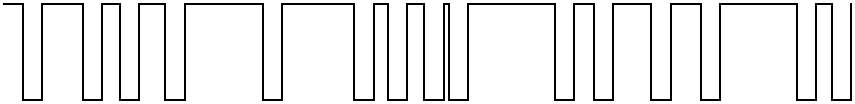

town is neatly laid out on a grid.

Here in London, the street pattern is irregular and so the transitions

in the square wave come at random seeming times, sometimes very close

together, sometimes very far apart.

Here in London, the street pattern is irregular and so the transitions

in the square wave come at random seeming times, sometimes very close

together, sometimes very far apart.

A scientist watching the wave would probably despair of finding any

pattern; it would look like a random circuit, driven by noise, triggered

perhaps by the arrival of cosmic rays from deep space, or the decay of

radioactive isotopes.

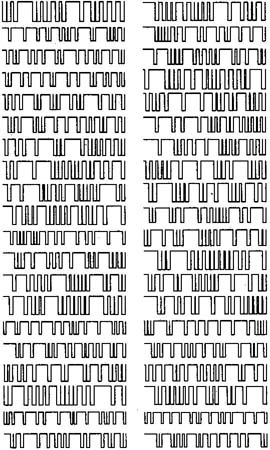

But if he had depth and ingenuity, it would be a different matter.

Depth could be obtained by putting a green light bulb on the head of

every person in London and then recording their tracings for a few nights.

The result would be a thick pile of graph paper tracings, each one as

seemingly random as the others. The thicker the pile, the greater the depth.

Ingenuity is a completely different matter. There is no systematic way

to get it. One person could look at the pile of square wave tracings and see

nothing but noise. Another might find a source of fascination there, an

irrational feeling impossible to explain to anyone who did not share it.

Some deep part of the mind, adept at noticing patterns (or the existence of

a pattern) would stir awake and frantically signal the dull quotidian parts

of the brain to keep looking at the pile of graph paper. The signal is dim

and not always heeded, but it would instruct the recipient to stand there

for days if necessary, shuffling through the pile of graphs like an autist,

spreading them out over a large floor, stacking them in piles according to

some inscrutable system, pencilling numbers, and letters from dead

alphabets, into the corners, cross referencing them, finding patterns, cross

checking them against others.

A scientist watching the wave would probably despair of finding any

pattern; it would look like a random circuit, driven by noise, triggered

perhaps by the arrival of cosmic rays from deep space, or the decay of

radioactive isotopes.

But if he had depth and ingenuity, it would be a different matter.

Depth could be obtained by putting a green light bulb on the head of

every person in London and then recording their tracings for a few nights.

The result would be a thick pile of graph paper tracings, each one as

seemingly random as the others. The thicker the pile, the greater the depth.

Ingenuity is a completely different matter. There is no systematic way

to get it. One person could look at the pile of square wave tracings and see

nothing but noise. Another might find a source of fascination there, an

irrational feeling impossible to explain to anyone who did not share it.

Some deep part of the mind, adept at noticing patterns (or the existence of

a pattern) would stir awake and frantically signal the dull quotidian parts

of the brain to keep looking at the pile of graph paper. The signal is dim

and not always heeded, but it would instruct the recipient to stand there

for days if necessary, shuffling through the pile of graphs like an autist,

spreading them out over a large floor, stacking them in piles according to

some inscrutable system, pencilling numbers, and letters from dead

alphabets, into the corners, cross referencing them, finding patterns, cross

checking them against others.

One day this person would walk out of that room carrying a highly

accurate street map of London, reconstructed from the information in all of

those square wave plots.

Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse is one of those people.

As a result, the authorities of his country, the United States of

America, have made him swear a mickle oath of secrecy, and keep supplying

him with new uniforms of various services and ranks, and now have sent him

to London.

He steps off a curb, glancing reflexively to the left. A jingling

sounds in his right ear, bicycle brakes trumpet. It is merely a Royal Marine

(Waterhouse is beginning to recognize the uniforms) off on some errand; but

he has reinforcements behind him in the form of a bus/coach painted olive

drab and stenciled all over with inscrutable code numbers.

"Pardon me, sir!" the Royal Marine says brightly, and swerves around

him, apparently reckoning that the coach can handle any mopping up work.

Waterhouse leaps forward, directly into the path of a black taxi coming the

other way.

After making it across that particular street, though, he arrives at

his Westminster destination without further life threatening incidents,

unless you count being a few minutes' airplane ride from a tightly organized

horde of murderous Germans with the best weapons in the world. He has found

himself in a part of town that seems almost like certain lightless, hemmed

in parts of Manhattan: narrow streets lined with buildings on the order of

ten stories high. Occasional glimpses of ancient and mighty gothic piles at

street ends clue him in to the fact that he is nigh unto Greatness. As in

Manhattan, the people walk fast, each with some clear purpose in mind.

The amended heels of the pedestrians' wartime shoes pop metallically.

Each pedestrian has a fairly consistent stride length and clicks with nearly

metronomic precision. A microphone in the sidewalk would provide an

eavesdropper with a cacophony of clicks, seemingly random like the noise

from a Geiger counter. But the right kind of person could abstract signal

from noise and count the pedestrians, provide a male/female break down and a

leg length histogram

He has to stop this. He would like to concentrate on the matter at

hand, but that is still a mystery.

A massive, blocky modern sculpture sits over the door of the St.

James's Park tube station, doing twenty four hour surveillance on the

Broadway Buildings, which is actually just a single building. Like every

other intelligence headquarters Waterhouse had seen, it is a great

disappointment.

It is, after all, just a building orange stone, ten or so stories, an

unreasonably high mansard roof accounting for the top three, some smidgens

of classical ornament above the windows, which like all windows in London

are divided into eight tight triangles by strips of masking tape. Waterhouse

finds that this look blends better with classical architecture than, say,

gothic.

He has some grounding in physics and finds it implausible that, when a

few hundred pounds of trinitrotoluene are set off in the neighborhood and

the resulting shock wave propagates through a large pane of glass the people

on the other side of it will derive any benefit from an asterisk of paper

tape. It is a superstitious gesture, like hexes on Pennsylvania Dutch

farmhouses. The sight of it probably helps keep people's minds focused on

the war.

Which doesn't seem to be working for Waterhouse. He makes his way

carefully across the street, thinking very hard about the direction of the

traffic, on the assumption that someone inside will be watching him. He goes

inside, holding the door for a fearsomely brisk young woman in a

quasimilitary outfit who makes it clear that Waterhouse had better not

expect to Get Anywhere just because he's holding the door for her and then

for a tired looking septuagenarian gent with a white mustache.

The lobby is well guarded and there is some business with Waterhouse's

credentials and his orders. Then he makes the obligatory mistake of going to

the wrong floor because they are numbered differently here. This would be a

lot funnier if this were not a military intelligence headquarters in the

thick of the greatest war in the history of the world.

When he does get to the right floor, though, it is a bit posher than

the wrong one was. Of course, the underlying structure of everything in

England is posh. There is no in between with these people. You have to walk

a mile to find a telephone booth, but when you find it, it is built as if

the senseless dynamiting of pay phones had been a serious problem at some

time in the past. And a British mailbox can presumably stop a German tank.

None of them have cars, but when they do, they are three ton hand built

beasts. The concept of stamping out a whole lot of cars is unthinkable there

are certain procedures that have to be followed, Mt. Ford, such as the hand

brazing of radiators, the traditional whittling of the tyres from solid

blocks of cahoutchouc.

Meetings are all the same. Waterhouse is always the Guest; he has never

actually hosted a meeting. The Guest arrives at an unfamiliar building, sits

in a waiting area declining offers of caffeinated beverages from a

personable but chaste female, and is, in time, ushered to the Room, where

the Main Guy and the Other Guys are awaiting him. There is a system of

introductions which the Guest need not concern himself with because he is

operating in a passive mode and need only respond to stimuli, shaking all

hands that are offered, declining all further offers of caffeinated and

(now) alcoholic beverages, sitting down when and where invited. In this

case, the Main Guy and all but one of the Other Guys happen to be British,

the selection of beverages is slightly different, the room, being British,

is thrown together from blocks of stone like a Pharaoh's inner tomb, and the

windows have the usual unconvincing strips of tape on them. The Predictable

Humor Phase is much shorter than in America, the Chitchat Phase longer.

Waterhouse has forgotten all of their names. He always immediately

forgets the names. Even if he remembered them, he would not know their

significance, as he does not actually have the organization chart of the

Foreign Ministry (which runs Intelligence) and the Military laid out in

front of him. They keep saying "woe to hice!" but just as he actually begins

to feel sorry for this Hice fellow, whoever he is, he figures out that this

is how they pronounce "Waterhouse." Other than that, the one remark that

actually penetrates his brain is when one of the Other Guys says something

about the Prime Minister that implies considerable familiarity. And he's not

even the Main Guy. The Main Guy is much older and more distinguished. So it

seems to Waterhouse (though he has completely stopped listening to what all

of these people are saying to him) that a good half of the people in the

room have recently had conversations with Winston Churchill.

Then, suddenly, certain words come into the conversation. Water house

was not paying attention, but he is pretty sure that within the last ten

seconds, the word Ultra was uttered. He blinks and sits up straighter.

The Main Guy looks bemused. The Other Guys look startled.

"Was something said, a few minutes ago, about the availability of

coffee?" Waterhouse says.

"Miss Stanhope, coffee for Captain Woe To Hice," says the Main Guy into

an electrical intercom. It is one of only half a dozen office intercoms in

the British Empire. However, it is cast in a solid ingot from a hundred

pounds of iron and fed by 420 volt cables as thick as Waterhouse's index

finger. "And if you would be so good as to bring tea."

So, now Waterhouse knows the name of the Main Guy's secretary. That's a

start. From that, with a bit of research he might be able to recover the

memory of the Main Guy's name.

This seems to have thrown them back into the Chitchat Phase, and though

American important guys would be fuming and frustrated, the Brits seem

enormously relieved. Even more beverages are ordered from Miss Stanhope.

"Have you seen Dr. Shehrrrn recently?" the Main Guy inquires of

Waterhouse. He has a touch of concern in his voice.

"Who?" Then Waterhouse realizes that the person in question is

Commander Schoen, and that here in London the name is apt to be pronounced

correctly, Shehrrn instead of Shane.

"Commander Waterhouse?" the Main Guy says, several minutes later. On

the fly, Waterhouse has been trying to invent a new cryptosystem based upon

alternative systems of pronouncing words and hasn't said anything in quite a

while.

"Oh, yeah! Well, I stopped in briefly and paid my respects to Schoen

before getting on the ship. Of course, when he's, uh, feeling under the

weather, everyone's under strict orders not to talk cryptology with him."

"Of course."

"The problem is that when your whole relationship with the fellow is

built around cryptology, you can't even really poke your head in the door

without violating that order."

"Yes, it is most awkward."

"I guess he's doing okay." Waterhouse does not say this very

convincingly and there is an appropriate silence around the table.

"When he was in better spirits, he wrote glowingly of your work on the

Cryptonomicon," says one of the Other Guys, who has not spoken very much

until now. Waterhouse pegs him as some kind of unspecified mover and shaker

in the world of machine cryptology.

"He's a heck of a fella," Waterhouse says.

The Main Guy uses this as an opening. "Because of your work with Dr.

Schoen's Indigo machine, you are, by definition, on the Magic list. Now that

this country and yours have agreed at least in principle to cooperate in the

field of cryptanalysis, this automatically puts you on the Ultra list."

"I understand, sir," Waterhouse says.

"Ultra and Magic are more symmetr

One day this person would walk out of that room carrying a highly

accurate street map of London, reconstructed from the information in all of

those square wave plots.

Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse is one of those people.

As a result, the authorities of his country, the United States of

America, have made him swear a mickle oath of secrecy, and keep supplying

him with new uniforms of various services and ranks, and now have sent him

to London.

He steps off a curb, glancing reflexively to the left. A jingling

sounds in his right ear, bicycle brakes trumpet. It is merely a Royal Marine

(Waterhouse is beginning to recognize the uniforms) off on some errand; but

he has reinforcements behind him in the form of a bus/coach painted olive

drab and stenciled all over with inscrutable code numbers.

"Pardon me, sir!" the Royal Marine says brightly, and swerves around

him, apparently reckoning that the coach can handle any mopping up work.

Waterhouse leaps forward, directly into the path of a black taxi coming the

other way.

After making it across that particular street, though, he arrives at

his Westminster destination without further life threatening incidents,

unless you count being a few minutes' airplane ride from a tightly organized

horde of murderous Germans with the best weapons in the world. He has found

himself in a part of town that seems almost like certain lightless, hemmed

in parts of Manhattan: narrow streets lined with buildings on the order of

ten stories high. Occasional glimpses of ancient and mighty gothic piles at

street ends clue him in to the fact that he is nigh unto Greatness. As in

Manhattan, the people walk fast, each with some clear purpose in mind.

The amended heels of the pedestrians' wartime shoes pop metallically.

Each pedestrian has a fairly consistent stride length and clicks with nearly

metronomic precision. A microphone in the sidewalk would provide an

eavesdropper with a cacophony of clicks, seemingly random like the noise

from a Geiger counter. But the right kind of person could abstract signal

from noise and count the pedestrians, provide a male/female break down and a

leg length histogram

He has to stop this. He would like to concentrate on the matter at

hand, but that is still a mystery.

A massive, blocky modern sculpture sits over the door of the St.

James's Park tube station, doing twenty four hour surveillance on the

Broadway Buildings, which is actually just a single building. Like every

other intelligence headquarters Waterhouse had seen, it is a great

disappointment.

It is, after all, just a building orange stone, ten or so stories, an

unreasonably high mansard roof accounting for the top three, some smidgens

of classical ornament above the windows, which like all windows in London

are divided into eight tight triangles by strips of masking tape. Waterhouse

finds that this look blends better with classical architecture than, say,

gothic.

He has some grounding in physics and finds it implausible that, when a

few hundred pounds of trinitrotoluene are set off in the neighborhood and

the resulting shock wave propagates through a large pane of glass the people

on the other side of it will derive any benefit from an asterisk of paper

tape. It is a superstitious gesture, like hexes on Pennsylvania Dutch

farmhouses. The sight of it probably helps keep people's minds focused on

the war.

Which doesn't seem to be working for Waterhouse. He makes his way

carefully across the street, thinking very hard about the direction of the

traffic, on the assumption that someone inside will be watching him. He goes

inside, holding the door for a fearsomely brisk young woman in a

quasimilitary outfit who makes it clear that Waterhouse had better not

expect to Get Anywhere just because he's holding the door for her and then

for a tired looking septuagenarian gent with a white mustache.

The lobby is well guarded and there is some business with Waterhouse's

credentials and his orders. Then he makes the obligatory mistake of going to

the wrong floor because they are numbered differently here. This would be a

lot funnier if this were not a military intelligence headquarters in the

thick of the greatest war in the history of the world.

When he does get to the right floor, though, it is a bit posher than

the wrong one was. Of course, the underlying structure of everything in

England is posh. There is no in between with these people. You have to walk

a mile to find a telephone booth, but when you find it, it is built as if

the senseless dynamiting of pay phones had been a serious problem at some

time in the past. And a British mailbox can presumably stop a German tank.

None of them have cars, but when they do, they are three ton hand built

beasts. The concept of stamping out a whole lot of cars is unthinkable there

are certain procedures that have to be followed, Mt. Ford, such as the hand

brazing of radiators, the traditional whittling of the tyres from solid

blocks of cahoutchouc.

Meetings are all the same. Waterhouse is always the Guest; he has never

actually hosted a meeting. The Guest arrives at an unfamiliar building, sits

in a waiting area declining offers of caffeinated beverages from a

personable but chaste female, and is, in time, ushered to the Room, where

the Main Guy and the Other Guys are awaiting him. There is a system of

introductions which the Guest need not concern himself with because he is

operating in a passive mode and need only respond to stimuli, shaking all

hands that are offered, declining all further offers of caffeinated and

(now) alcoholic beverages, sitting down when and where invited. In this

case, the Main Guy and all but one of the Other Guys happen to be British,

the selection of beverages is slightly different, the room, being British,

is thrown together from blocks of stone like a Pharaoh's inner tomb, and the

windows have the usual unconvincing strips of tape on them. The Predictable

Humor Phase is much shorter than in America, the Chitchat Phase longer.

Waterhouse has forgotten all of their names. He always immediately

forgets the names. Even if he remembered them, he would not know their

significance, as he does not actually have the organization chart of the

Foreign Ministry (which runs Intelligence) and the Military laid out in

front of him. They keep saying "woe to hice!" but just as he actually begins

to feel sorry for this Hice fellow, whoever he is, he figures out that this

is how they pronounce "Waterhouse." Other than that, the one remark that

actually penetrates his brain is when one of the Other Guys says something

about the Prime Minister that implies considerable familiarity. And he's not

even the Main Guy. The Main Guy is much older and more distinguished. So it

seems to Waterhouse (though he has completely stopped listening to what all

of these people are saying to him) that a good half of the people in the

room have recently had conversations with Winston Churchill.

Then, suddenly, certain words come into the conversation. Water house

was not paying attention, but he is pretty sure that within the last ten

seconds, the word Ultra was uttered. He blinks and sits up straighter.

The Main Guy looks bemused. The Other Guys look startled.

"Was something said, a few minutes ago, about the availability of

coffee?" Waterhouse says.

"Miss Stanhope, coffee for Captain Woe To Hice," says the Main Guy into

an electrical intercom. It is one of only half a dozen office intercoms in

the British Empire. However, it is cast in a solid ingot from a hundred

pounds of iron and fed by 420 volt cables as thick as Waterhouse's index

finger. "And if you would be so good as to bring tea."

So, now Waterhouse knows the name of the Main Guy's secretary. That's a

start. From that, with a bit of research he might be able to recover the

memory of the Main Guy's name.

This seems to have thrown them back into the Chitchat Phase, and though

American important guys would be fuming and frustrated, the Brits seem

enormously relieved. Even more beverages are ordered from Miss Stanhope.

"Have you seen Dr. Shehrrrn recently?" the Main Guy inquires of

Waterhouse. He has a touch of concern in his voice.

"Who?" Then Waterhouse realizes that the person in question is

Commander Schoen, and that here in London the name is apt to be pronounced

correctly, Shehrrn instead of Shane.

"Commander Waterhouse?" the Main Guy says, several minutes later. On

the fly, Waterhouse has been trying to invent a new cryptosystem based upon

alternative systems of pronouncing words and hasn't said anything in quite a

while.

"Oh, yeah! Well, I stopped in briefly and paid my respects to Schoen

before getting on the ship. Of course, when he's, uh, feeling under the

weather, everyone's under strict orders not to talk cryptology with him."

"Of course."

"The problem is that when your whole relationship with the fellow is

built around cryptology, you can't even really poke your head in the door

without violating that order."

"Yes, it is most awkward."

"I guess he's doing okay." Waterhouse does not say this very

convincingly and there is an appropriate silence around the table.

"When he was in better spirits, he wrote glowingly of your work on the

Cryptonomicon," says one of the Other Guys, who has not spoken very much

until now. Waterhouse pegs him as some kind of unspecified mover and shaker

in the world of machine cryptology.

"He's a heck of a fella," Waterhouse says.

The Main Guy uses this as an opening. "Because of your work with Dr.

Schoen's Indigo machine, you are, by definition, on the Magic list. Now that

this country and yours have agreed at least in principle to cooperate in the

field of cryptanalysis, this automatically puts you on the Ultra list."

"I understand, sir," Waterhouse says.

"Ultra and Magic are more symmetr